Portugal was still grappling with the harrowing effects of the financial crisis when, in July 2014, a(nother) scandal hit the country’s headlines and beyond. Banco Espírito Santo (BES)—one of Portugal’s largest private banks back then—was at the epicentre.

The first alarm bell went off when the bank, owned by the Espírito Santo family, announced a bigger-than-expected loss of €3.6bn for the first six months of 2014 due to “extraordinary events”. This loss eliminated BES’s capital buffer of nearly €2.1bn, dropping it below the minimum threshold required by regulators.

The second alarm bell went off when parent companies linked to the Espírito Santo family, who had built a global financial empire over a century and a half, sought protection from creditors. After intense pressure from regulators, Ricardo Espírito Santo Salgado, then both the bank’s chief executive officer (CEO) and head of the family holding company, Espírito Santo International, resigned from the CEO post.

Within a month, Espírito Santo International filed for bankruptcy, crumbling under €6.4bn of debt. In August, Portugal’s central bank rescued BES and restructured it by splitting it into two: the “good bank”, called Novo Banco, where quality assets and liabilities were placed, and the “bad bank”, BES, which kept the “toxic” liabilities and assets.

Don’t have time to read the whole blog entry? Then watch our “Blog in 1 minute” video for a quick summary of its main points:

Most importantly, tens of thousands of small investors lost their money. We couldn’t find more up-to-date information, but according to a Reuters article from 2014, “shareholders and investors in the family companies and Banco Espírito Santo have lost more than 10 billion euros, making this one of Europe’s biggest corporate collapses ever.” Can you imagine losing your money in the blink of an eye?

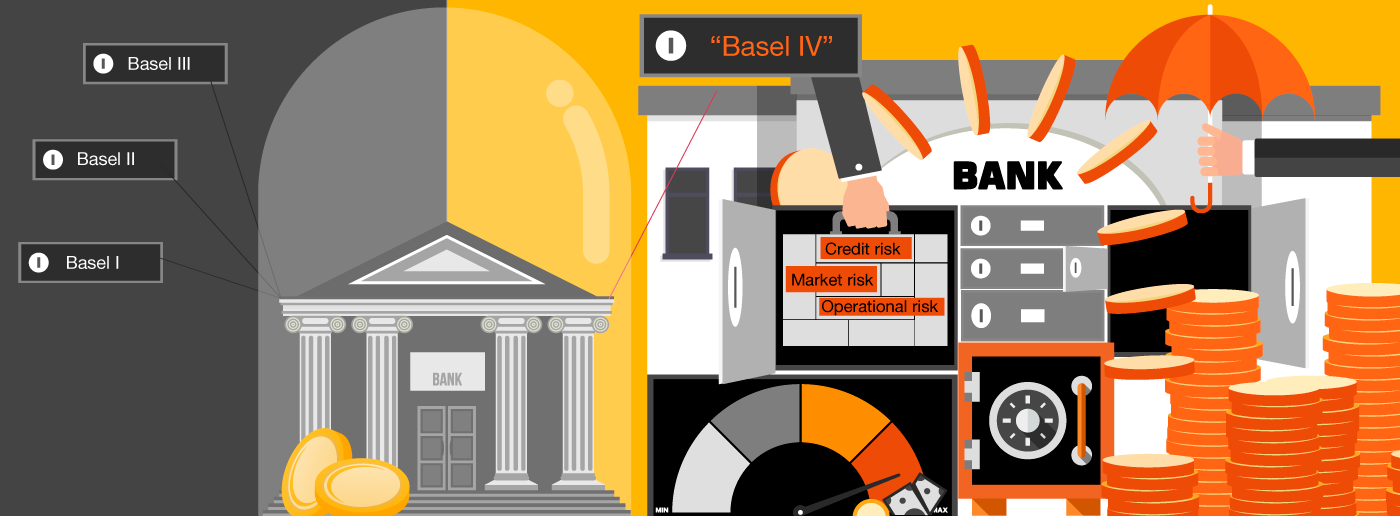

However, we could argue that, more than savings, those affected lost their trust in banks, account managers, policymakers and supervisors. Basically, in the “system”. Interestingly, this event took place soon after Basel III came into force, which was a set of recommendations—quite ironically—meant to prevent this type of situation. This only showed that further work was needed. That’s when ‘Basel IV’ comes into play.

Put simply, ‘Basel IV’ is a term for a standard whose objective is to mitigate risks in the banking sector by further reinforcing banks’ capacity to withstand potential financial shocks. But ultimately, the goal is to protect people’s savings and the real economy, and prevent grim stories like BES’s from happening again.

In this blog, we explain in more detail what ‘Basel IV’ is, its context, the challenges it brings to banks and how they can get ready for it. Full disclosure: this is probably not the most exciting and straightforward topic for the layman or woman, but trust us, you will be absorbed in it by the end of our blog. After all, it affects all of us.

In fact, the Basel standards were, once upon a time, a relatively simple subject to grasp. But because these standards have been amended so many times since their inception, the topic has become complex over time. To further complicate matters, there isn’t a consolidated version of the current text at European Union (EU) level. Hence, if you are a newbie or haven’t been able to keep a tab on the changes, you can easily get lost. But fret not. We are here to guide you through it.

What’s in a name: How Basel came to life

It all started with—yes, you guessed it—Basel I in 1988. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), located in—yes, you guessed it again—Basel, published the first Basel Accord, a set of minimum capital requirements for banks (we will get into this later), to ensure fair and equitable competitiveness between banks.

This committee of currently 45 members—we can call them the Wise Men (and Women), if you will—comprises central banks and bank supervisors from 28 jurisdictions, and is the primary global standard setter for the economical regulation of banks.

However, the Basel Committee doesn’t have any legal powers. Meaning, their decisions aren’t binding. It’s up to each country or region to decide to apply the requirements locally. Still, it can assess how these countries and regions have implemented them. In other words, they can name and shame.

In the European Union, the Basel recommendations are turned into a legal framework at EU level. This is done via two instruments: the Capital Requirements Regulation and the Capital Requirements Directive. The former, as a EU law, doesn’t need to be transposed into national law while the latter, as a directive, does. The UK, US and Singapore have a similar approach as the EU, but with their own deadlines.

So, after Basel I came Basel II, in 2008 in the EU. Its goal was completely different from its predecessor: it aimed to improve the banking sector’s robustness, requiring banks to have capital liquidity—a capital buffer—proportional to the risks they were taking.

Note: They also needed (and still need) to limit the size of their balance sheet compared to their capital (that is, limit leverage), but since the rules around it remain the same with ‘Basel IV’, we won’t cover it further in this blog.

Buffering up: The link between capital and risk

The same way people have savings for a rainy day, banks have capital (at least since the Basel standards’ inception). Capital is money that can absorb losses for banks. Indeed, if a bank makes a loss, it’s the shareholders who bear the brunt, as they own the capital invested in the bank. Depositors, like you and us, with savings accounts, are typically shielded from such losses.

Remember BES? Their losses surpassed their capital buffer and, unfortunately for shareholders and investors, they literally paid the price.

Hence, the more risk a bank takes, the more capital it needs as a buffer to protect depositors. On the flip side, when banks have a big amount of capital, it essentially lies dormant. This isn’t good for them because money that is asleep is money that isn’t profitable. That’s why banks can never be totally “safe”. Or else, their existence would be futile.

So, the Basel standards aim to strike a balance, ensuring safety without compromising economic viability—a delicate equilibrium where prudence meets profitability. Sometimes, however, measures aren’t strong enough to cushion unprecedented and unexpected events. That was the case with Basel II and the financial crisis in 2008-2009.

From Basel III to Basel IV

When Basel II didn’t prevent the banking collapse during the financial crisis in 2008-2009, the BCBS responded by developing new recommendations known as Basel III that came into force in 2014. It introduced measures to bolster both the quality and quantity of regulatory capital, fortifying risk coverage, and mitigating systemic risks. As a result, banks found themselves facing a tsunami of regulations.

The good news is that, since then, banks have been diligent pupils. And especially during COVID-19, they outdid themselves by being part of the solution rather than the problem, supporting the troubled economy.

Still, Basel III eventually became perceived as too standard, not allowing enough differentiation between banks regarding their risk quantification. This led to discussions and revisions, informally referred to as ‘Basel IV’.

So ‘Basel IV’ are new recommendations that include reforms to increase banks’ risk sensitivity and on how to quantify them. In more technical terms, these recommendations concern the calculation of banks’ risk-weighted assets and thus their capital ratios.

Side note: We say “informally referred to as ‘Basel IV’” because that’s not the official terminology—and that’s why we keep using single quotation marks. Those within the banking industry affectionately dub it as such, believing it rightfully deserves the title due to the profound changes it introduces—the most significant in the past two decades.

As for its official name, here’s the answer: In the European Union, it’s called “Basel III finalisation in the EU” while in the UK it’s Basel 3.1, and in the US—unsurprisingly, much more dramatic—it’s “Basel III Endgame”. But the actual bankers go for ‘Basel IV’ instead, because the magnitude of the changes is really significant.

Basel IV in more detail: it’s all about risk

The ‘Basel IV’ rules will require a more detailed calculation of banks’ risk-weighted assets so that it’s closer to the current economic reality. For instance, they will instruct banks that lending to Corporation A will require them to have a specific amount of capital, while a loan to the Central Bank of Luxembourg will demand no capital requirement due to its perceived risk equivalence to the state (remember that the Grand Duchy has a triple A credit rating).

By the way, when we talk about risk, we focus on the three main types all banks are exposed to:

- Credit risk: It stands out as the foremost concern for banks. It entails the risk of lending money to individuals or entities who fail to repay, resulting in financial loss for the lender.

- Market risk: It encompasses exposure to fluctuations in financial markets, whether through stock market investments or foreign exchange dealings. For instance, conducting business with the US exposes entities to currency exchange rate fluctuations, potentially resulting in unexpected losses.

- Operational risk: It delves into the intricate interplay between human factors and systemic vulnerabilities within an organisation’s operations. This includes IT issues, infrastructure issues, fraud, human error, procedural deficiencies, and control lapses.

Banks will have to measure these risks by putting numbers on them to compare their levels. As you can imagine, these rules span hundreds of pages to ensure such a thorough risk assessment and management.

On this note, the changes ‘Basel IV’ introduces will clearly impact banks’ strategies and their business models of the future, generating new challenges for them. These fall into two main categories: economic and operational.

The challenges for banks: economic and operational

At an economic level, the primary concern for banks is that the new standards could result in significantly higher risk assessments, requiring them to hold more capital (that they will have to seek from their parent group or shareholders).

In reality, this will be the scenario for the majority of banks—which isn’t an ideal one. Conversely, a small subset of banks will find themselves needing less capital, which poses no issue for them—actually, quite the opposite.

A word of caution though: we can’t generalise. That’s exactly the purpose of ‘Basel IV’, which, by enhancing risk sensitivity, will automatically lead to various business models having different increases or decreases in risk. Therefore, each bank needs to conduct simulations tailored to its specific activities to accurately estimate the impact of the new regulations.

Given that the main change revolves around quantifying risks, there’s also an operational impact. Banks will have to update their systems to collect new data, while also training their staff and adjusting their processes accordingly. Additionally, they will need to submit new reports to the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF), Luxembourg’s financial regulator, and to the European Central Bank (the Eurozone’s banking supervisor) to disclose their revised figures.

This can seem daunting to banks, however they can—and should—already take some steps to gear up for the upcoming changes.

How and when to get ready for ‘Basel IV’

Before we get to the how, let’s tackle the when. At EU level, ‘Basel IV’ encompasses the implementation of two instruments: The Capital Requirements Regulation III (CRR III) and the Capital Requirements Directive VI (CRD VI). They both should be voted on in April this year.

This means the CRR III should come into force in January 2025, leaving banks with little time to prepare—around eight months to be precise. For the CRD VI, however, they will likely have another year—give or take—to gear up, as it will still need to be transposed into national law.

That said, most of the technical details lie within the CRR III itself. The directive, on the other hand, typically focuses on granting more authority to bodies like the CSSF or the European Central Bank to ensure the regulation’s effective implementation.

Here it’s worth noting that the UK has announced its intention to adopt these regulations by July 2025, and we anticipate the US following suit around the same time. This could potentially put European banks at a slight disadvantage as they would need to comply six months earlier than their counterparts.

Therefore, banks in the EU should start preparing now. In fact, many banks began preparations as early as 2023. They could do so because the regulations have been finalised since December 2023 and, according to authorities, April’s vote is mostly political.

Some large banks have started even earlier (three years ago) since—and all banks should keep this in mind—this endeavour can be demanding and take time. It all depends on a bank’s number of activities.

Now that you know that there’s nothing stopping you from starting the implementation, you may be wondering how to go about it. Well, you need to address both economic and operational impacts we mentioned earlier.

First, do the impact assessment. As we’ve said, the impact of the regulations will vary between banks, so each one needs to conduct its own simulation to assess whether, for instance, it needs to boost its capital reserves or not. The second step is getting into the nitty-gritty of the IT implementation.

The ripple effects of ‘Basel IV’

‘Basel IV’ is probably not a revolution, but it’s definitely a strong evolution to further strengthen banks’ robustness. In the grand scheme of things, its ripple effect is immense because it also protects people’s savings and the economy.

Perhaps as important, and coming back to the Banco Espírito Santo scandal, the new standards can contribute to continuing restoring trust in the banking sector and all the stakeholders who are part of the “system”.

Hence, banks should definitely think about fulfilling their regulatory obligations, but also consider the broader implications. Their reputation and the trust from their clients are at stake. And ultimately, it’s about how their actions, whether positive or negative, impact people’s lives and the level of confidence they inspire.

So, the time to start is now.

What we think

“In my view, this is probably the most significant change to the banking risk management regulation in the nearly 20 years since Basel II was first designed.”

Jean-Philippe Maes, Advisory Partner at PwC Luxembourg